Sreshta Rit Premnath on finding hope at the margins

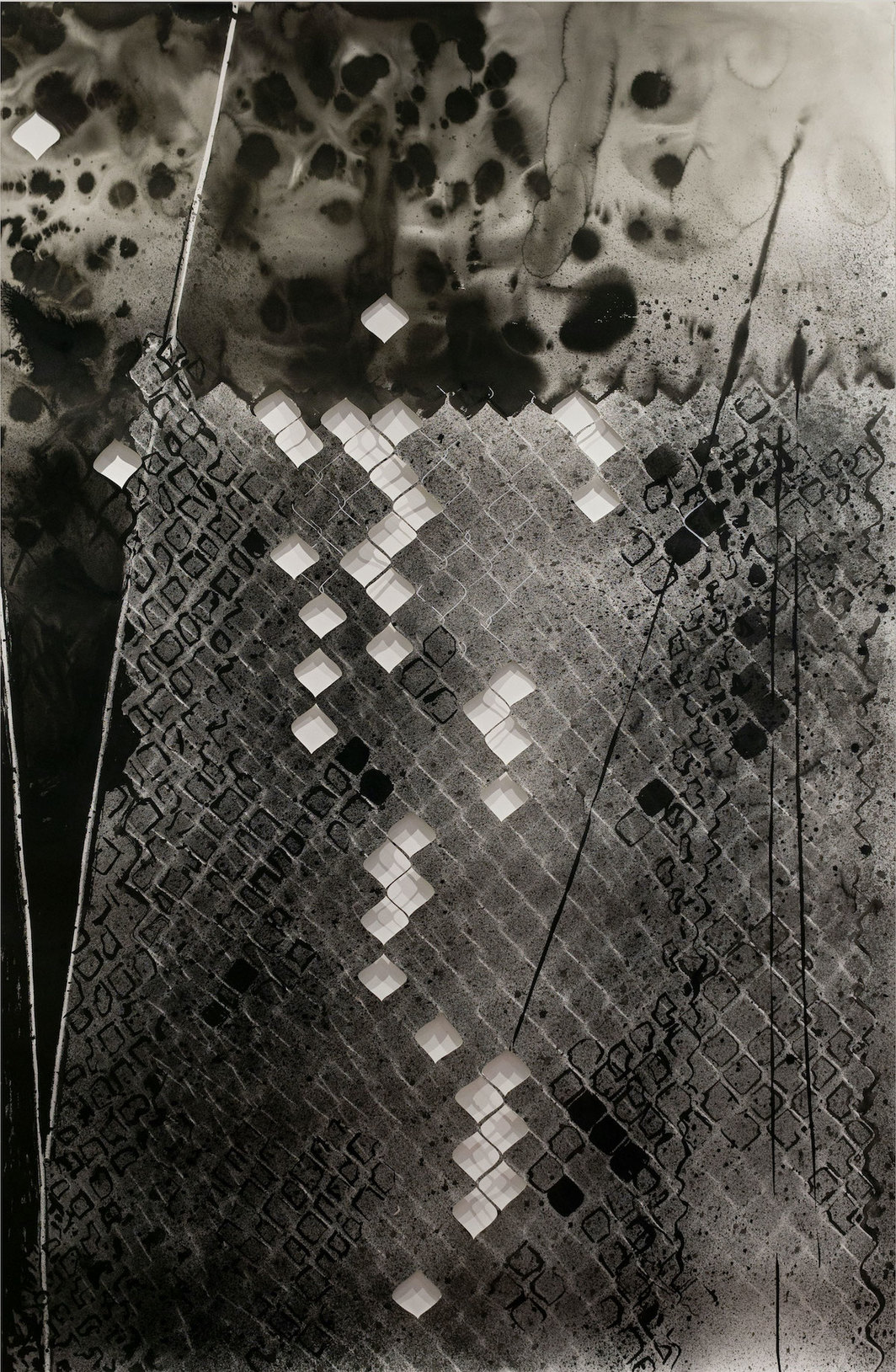

Sreshta Rit Premnath abstracts materials associated with the architecture and institutions of confinement and control—chain-link fencing, metal barriers, aluminum sheets, Mylar blankets, foam mattresses—into floating signifiers that he recombines into installations at once topographical and quietly theatrical. Below, Premnath discusses two related exhibitions, both titled “Grave/Grove” and currently on view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center until February 13, 2022, and Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center until February 27, 2022, where his austere sculptures become unlikely hosts to various vegetal life forms growing throughout the galleries.

AS A MIGRANT WITH AN INDIAN PASSPORT, I have been subjected to all kinds of bureaucratic delay and humiliation at the border. The fact that a state defines itself by who it allows in and who it keeps out is very palpable and concrete for me. I was horrified by the pictures of detention camps on our Southern border. As a US citizen and a taxpayer now, I too am implicated in our country’s inhumane treatment of people fleeing extreme hardship. I therefore approach this issue from within and without.

The exhibitions’ shared title, “Grave/Grove,” pairs two words that at first appear to be opposites. It also appears in one of a series of text pieces scattered throughout the shows that resemble exit signs, which are, for me, a way to mark an opening between inside and outside. Each piece is a two-word poem with one term illuminated on each side of the sign, creating dyads that provide conceptual anchors to the viewer. At the List they include “Insist/Exist,” “Wait/Wake,” “Escape/Arrive,” and “Grave/Grove,” which appears again at the CAC alongside “Fall/Land,” “Lean/Hold,” and “Home/Hole.” The installations contain aluminum forms that resemble unfolded cardboard boxes, like those on which homeless people sleep in New York. They reference a commonplace practice of provisional habitation while also drawing the spectator in through the metal’s reflectivity. By rendering a found form in a different material, I supplement its original significance with other possible associations, from the cold austerity of a holding cell to the ethereal glow of a reflecting pool. At the List, figurative sculptures made from foam and plaster that I call “slumps” sit and lie in these metal forms, while in Cincinnati they are suspended by chain-link slings. Foam, which usually supports the body, implies softness and receptivity. In my sculptures I transform it into bodies that are barely able to support themselves.

These “slumps” have featured in other series, like “Kettling,” 2021, where the twisted, brittle bodies are corralled but also supported by hard metal barriers, examining the relationship between popular dissent and the often violent strategies used to control it. In “Those Who Wait,” 2019, I used the architecture of prisons and detention camps as points of departure to examine the dynamic between structures of confinement and the bodies trapped by them. In all these cases, by taking a material out of its reality and abstracting it, I imbue it with new phenomenological and symbolic connotations. Abstraction is not the opposite of the real but a means of understanding reality. We engage in abstraction when we theorize about the world. It’s a way of making sense of our environment—both intellectually and in a way that is embodied and felt.

Last spring, as I and many of my loved ones in the US and India received our Covid-19 vaccinations, the snow melted in New York and new growth emerged everywhere. I was especially moved by the wild plants that sprouted along street edges and out of sidewalk cracks. In a city inured to the constant wail of ambulances, the sprouting of life felt like a good omen. Amid the suffering and death caused by the pandemic, Hannah Arendt’s call for a philosophy of “natality” in The Human Condition (1958) rang true. Instead of following a lineage of philosophers who understood death to be the principal threshold of human understanding, Arendt proposed that we consider birth. A newborn is a stranger to the world and open to seeing it anew. I wanted to create an installation in which a burst of greenery emerged from a cold and inhospitable context. The plants in the exhibitions are considered weeds—vegetal life that we deem undesirable and out of place. Indeed, it is the out-of-place-ness of weeds, of migrants, to which I am drawing attention. We immigrants often inhabit the periphery of society and are unable to actively participate in the political process, yet we make lives and livelihoods in these margins, and from that vantage reimagine what our newly adopted home can be. “Grave/Grove” is a way of thinking these two ideas—social death and political possibility—together.

— As told to Murtaza Vali