I Can Because You Do

2016 Parsons MFA Thesis Exhibition

“Without even leaving, we are already no longer there.”

Nikolai Gogoli

The theorist Paul Virilio uses the term meeting at a distance to describe being here and elsewhere – at the same time – an apt description of real time as we experience it in contemporary society. We are often in two places at once, an experience that is facilitated by rapidly developing teletechnologies.

Virilio’s term is also an eloquent description of the MFA experience. A diverse group of artists are brought together for two years. Time flies by as they investigate their art practice, exchange ideas, receive critical feedback, and strive to maintain connections to their families and friends back home – or not. Meanwhile the artists’ ideas are changing. Perhaps they are influenced by expectations, experiences of cultural translation, and new voices.

The title for this exhibition is borrowed from a passage in the essay Existential Exuberance written by the critic Jan Verwoert. In it, he ruminates on the culture of high performance and its pervasive demands. He thinks through the fear of influence, and proposes ‘moving towards a politics of dedication’. Verwoert writes, “To feel inspired essentially means to realize ‘I Can because You Do’. Any form of work that unfolds through addressing the work of others (including this essay) thrives on this sensation.”ii

If we accept “I Can because You Do” as a dedication, then the temptation might be to attribute the dedication solely to the MFA community. While it is a rich possibility that the artists have inspired (and possibly antagonized, refuted, ignored, plagiarized, supported and adored) one another, this exhibition is not based on contrived ideas about community and art making. Any overindulgence in that regard would undermine the risks incurred by making art full-time – which these artists heartily take on – as well as the gifts that such community affords, and the effort that it takes to engender them. The power of the phrase exists, in part, in its suggestive capacity – it’s there for you in the way you need it to be. Sometimes it may speak to a broader socio-political or cultural phenomenon. Other times it offers insight into the systems, alliances, structures and forms of critique that the artists engage. In some instances, it recognizes the artist’s relationship with remarkable individuals.

Umber Majeed works from a collection of photographs taken by her grandfather in the 1980s in Pakistan. As an amateur photographer, he documented his home, neighborhood, and Faisal Mosque. In her video, Majeed uses images of the national mosque (monument) in the city of Islamabad to explore national identity, the passage of time and displacement in a postcolonial world. Majeed also creates pencil drawings of photographic material such as film packages and date stamps on the backs of printed photos, evoking tactile memories of a recent time.

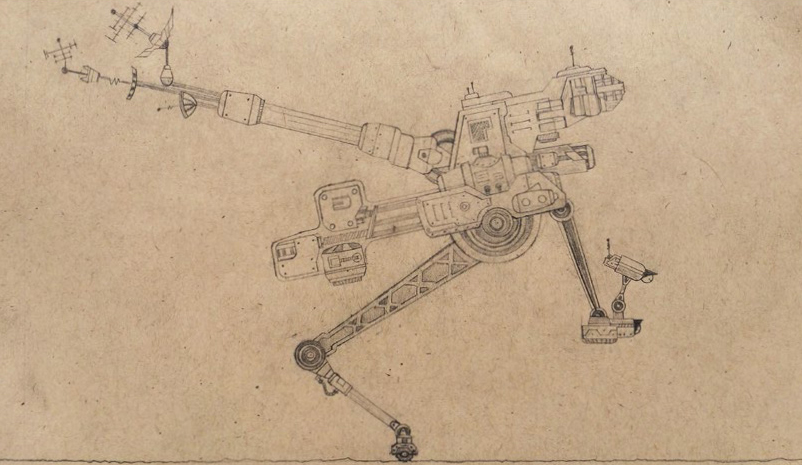

Eleana Antonaki draws fictional objects to encapsulate her family’s tradition of planting a Persian Silk tree for every migratory relocation they have undertaken – within Turkey and from Turkey to Greece. These relocations took place during historical events such as the Greek/Armenian genocide. With each displacement a seed has been buried, which continues to grow after the family moves on, like a memory. Antonaki is influenced by the ever-evolving nature of gardens, and her drawings of objects float in a field of mossy grey-green paint.

Leonie Cicirello has many ‘ransom photos’ of her cat – all of them taken by her parents, who use them as “a conduit to force communication”. In each photo, the happy captive lounges in a variety of poses: stretching, scratching, hunting. But it is the artist who is being hunted. Cicirello recounts how each image is imbued with questions, concerns and varied emotional approaches from her parents. Her pet is a conduit. In response, Cicirello has used Wite-Out to scratch out the cat’s eyes, symbolically severing the psychic connection her parents hope to build, and the insight into her life.

The phrase, ‘I Can because You Do’ offers power through the conjunctive, and indeed many of the artists in this exhibition explore ideas that exist in the and, with, through.

In her text paintings, Liona Robyn creates what she refers to as ‘abstract minimal pidgin’ to complicate the ongoing relationship of European modernism and Afro-modernism, in linguistic and visual terms. The phonetic phrase /ho͞o/ /nō/ /nō/ /ɡō/ /nō/ is written in thick acrylic paint directly onto the gallery wall, and then covered with a coat of wall paint. The small text painting is opaque and barely visible to the casual eye. It rises off of the wall like a scar. The phonetic phrase is borrowed from Fela Kuti’s song, who no know go know. A Nigerian musician and iconic figure within postcolonial Africa, Kuti was known for choosing to sing in pidgin. Elsewhere in the gallery, floating title cards invite the viewers to question their own position within the space.

Rea Chen’s daily dedication takes on the conjunctive is a different way. ‘The Coincidence Diary’ is a ritual practice of observation, collection, and release. Chen gathers and repurposes small objects that she finds in subways, parks and stairwells. Comprised of the detritus of urban life, her sculptures are created from mussel shells, feathers, broken plastic toys, and ticket stubs. These constellations of found objects are brought together temporarily: they are not welded, glued, or stapled. After a short shelf life Chen releases them back into the world, placing them at bus stops, under rocks or by fire hydrants for the observant passersby.

Ryota Sato engages an aggregate of substances, images and sounds to challenge our perception of nature, which is presented here in various processed forms. It seems the human experience of nature is hybrid – constructed, mediated, and filtered through different ideological proclivities. Extrusion aluminum frames Sato’s installation, while a combination of source materials (computer monitors, stones, wood sticks, slates of marble, cables, emergency blankets) and artworks (digital prints, videos, drawings) activate the structure to complicate any predetermined distinctions between the organic and the fabricated.

Saul Sanchez enters words into the Google search engine on his phone before he creates oil paintings on raw linen. Temporary compositions of colored squares and rectangles appear while the images upload. This is the basis for his paintings – a moment when the connection between words and images is suspended. Sanchez explores negative space’s physical holdings and conceptual envelope. Alongside painting are a series of deconstructed paper sculptures made from the negative space of animal conditioning chambers and a musical score composed of inverted note systems, which emits from an amp. Bringing these intervals together in a wall-mounted installation, he translates an experience of indeterminacy.

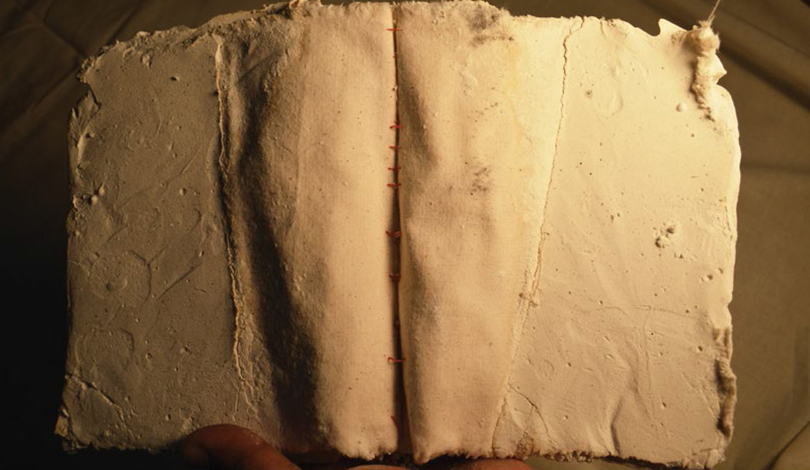

Julias John Alam is creating an archive of books that are burned or constructed out of cloth and stitched with red thread. The oversized books are sometimes sealed in concrete, caked in charcoal or simply left open for people to flip through their empty pages. These books memorialize those who have died as a result of the Blasphemy laws in Pakistan. In Alam’s artwork there are no words. The lack of text reminds us that books, like bodies, have physical presence. Their mutability is an act of withdrawal, a radical reduction that draws on an engagement with minimal forms and processes of material transformation.

Virilio often writes about causality. He has been called the theorist of disasters, linking his study of accidents to the notion of speed and the acceleration of history and of reality. Famously, he opined: “The invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck”. Here again, conjunctive enters in new terms.

In 1996 the rocket Ariane 5 exploded during its launch at the European Space Agency in Kourou, French Guiana. The explosion was caused by a single error embedded in the software used during the ignition process. Oscar Gracida is interested in precisely these types of contingencies. He has scripted the accident, as it was reported in real time by the computer. It is as if we are reading notes from a logbook. The mechanical narrator reports the error, as any other banal system malfunction. Gracida’s two-channel video analyzes a specific case of erratic software behavior. By reporting a significant, international event without any narrative spectacle, Gracida reflects on the kinds of logics that our everyday technological systems depend on.

Vered Snear appropriates Youtube tutorials as a genre in order to investigate the relationship between technology and culture. In her scripted video, Snear examines the role of language within this framework to uncover our own habits of interpellation. With media becoming increasingly more life-like, and life adapting to the logic of media, it is difficult to identify and think critically about the ways in which software interfaces, including Operating Systems and Internet Browsers, structure and monopolize our experience. Snear exploits the conventions of her source material to create discontinuities that critique the determined narratives and socio-psychic experience found in Internet culture.

Joseph Pastor explores material processes by staging various interactive scenarios, performances and modes of social exchange. Centered on the making or fabrication of objects, these activities emphasize the role of commodity, labor and participation through contractual agreements. Borrowing the language of store displays, Pastor offers for purchase a carefully crafted egg-like object in a custom built wooden box. The purchase price is based on a calculation of fair labor costs. Within the object is a small scroll, with a handwritten story, and it is up to each purchaser if they will crack open the egg to see what’s inside.

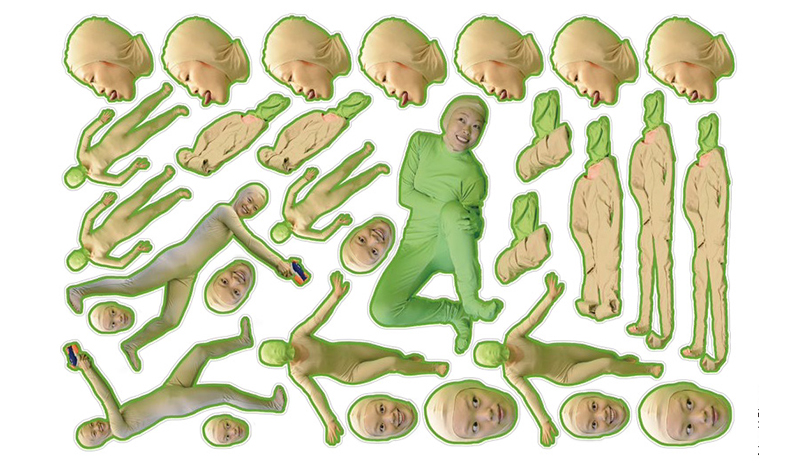

Employing cheery marketing strategies and visual tactics that typically promote an “all organic lifestyle”, Ingrid Zhuang takes the human body through a process of metamorphosis from fish to broccoli, then from human flesh to roasted chicken to piglets, but not before a human figure is decapitated by a vegetable grater. Zhuang’s five-minute video combines an array of 2D image collages, animated GIF and green-screen techniques to illustrate human fallacy and our tentative grip on the environmental whole. She complicates the idea that humans are ultimate consumers at the top of the food chain, by placing us within a larger system of idiosyncratic relations.

Fernando do Campo’s interest in non-native bird species, and in particular, the House Sparrow, follows multiple trajectories: linguistic, historical, and fictive. His artworks signify and explore postcoloniality and the impact of humans on the planet. Within the entity House Sparrow Society for Humans, which he formed in 2015, do Campo explores a breadth of source materials and research, including migratory bird patterns and legacies of abstract painting. do Campo’s body of work moves between formal vocabularies of abstraction and display, frequently employing language itself as a tool to explore visuality.

Alex Sheriff’s video and audio guide takes us through a playfully crafted scenography populated by lumpy plants and affable dinosaurs. The video is projected onto a curved wall that mimics the dioramas in natural history museums. But here, instead of looking through glass, we are embraced by a new world. Borrowing freely from pseudo-science and mythology, Sheriff’s land combines thick jungles, ocean bottoms, and deep space in one mauve-infused moonscape. Systems of categorization that determine disciplines like ecology and ethnography are beside the point. Aping Saturday morning cartoons and elementary school textbooks, Sheriff asks us to reconsider our position as humans at the top of the hierarchy.

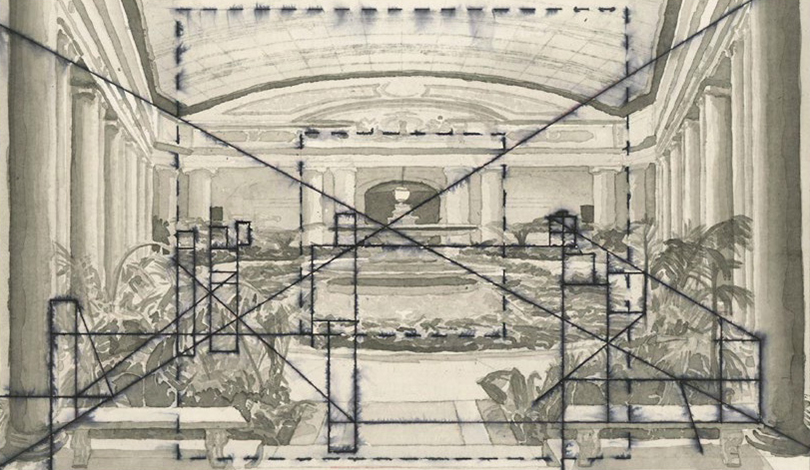

Perspectival shifts – across space and time – are at the core of Weston Frazor’s paintings, which in this instance offer us a glimpse into two prominent New York museums: the Garden Court at the Frick Collection and the Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Frazor has collaged multiple photographs of each room, taken from different vantage points, which are then painted and overlaid with a grid system to notate where bodies once stood. The method creates subtle disproportions, undoing the notion that any one perspective might allow for a complete view.

Appropriating digital technology as part of her painting technique, Tao Xian uses a scanner to digitize portraits. During this process, the artist moves images around on the scanner bed, activating the light sensors to create glitches and distortions. As a result, faces are fragmented into strips of light and viscous abstractions. Xian renders these in paint, with pallets that are informed by the colors of the scan. Both the paintings and scans are created over an arc of time, as opposed to the click of a shutter.

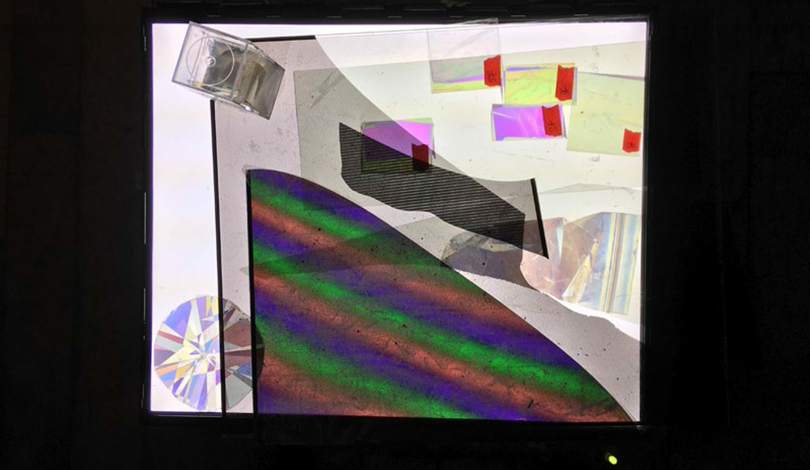

By processing light through several layers of glass and diffusion film, computer screens mediate our interactions with the digital world. William Lee literally deconstructs this, taking apart each component of LCD screens to reveal the mechanics within. Cracked open, dissected, and presented as sculptures, we approach the substrate like rocks on an archeological dig. Lee uses these materials, embedded within the apparatus, to activate a visual language and in doing so, he reminds us of the extreme (often invisible) labor it takes to produce them in the first place.

In thinking about the digital world, the software and hardware that mediates it, Lee wrote the following in his exhibition proposal for I Can Because You Do: “It is assumed that the digital is bereft of materiality, context, and integrity, but I contest that it is as intimate and indexical of an event as a finger marking sand. It is only a matter of learning and understanding the language of its trace.”iii

Lee’s reference to sand is more than poetic. Heating ordinary sand at extremely high temperatures makes glass, which is a key material in computer screens. It’s an interesting coincidence that Virilio worked as a stained glass artist after World War II alongside Henri Matisse and Georges Braque. Virilio often observes the “evidences” of contemporary life. The act of observation is also at the root of these artists’ practices, thankfully, as it may be one of the best tools we have at our disposal to address what Verwoert calls “the experience of divided, alienated time”.

Alhena Katsof

i As quoted by Paul Virilio, “The Third Interval,” in Open Sky (New York: Verso, 1997).

ii Jan Verwort, “Exhaustion and Exuberance,” in Tell Me What You Want, What You Really, Really Want (Rotterdam & Berlin: Piet Zwart Institute & Sternberg Press, 2010).

iii William Lee, Thesis Exhibition Proposal, Parsons Fine Arts, MFA Thesis Exhibition, 2016.

Download Pdf: LINK