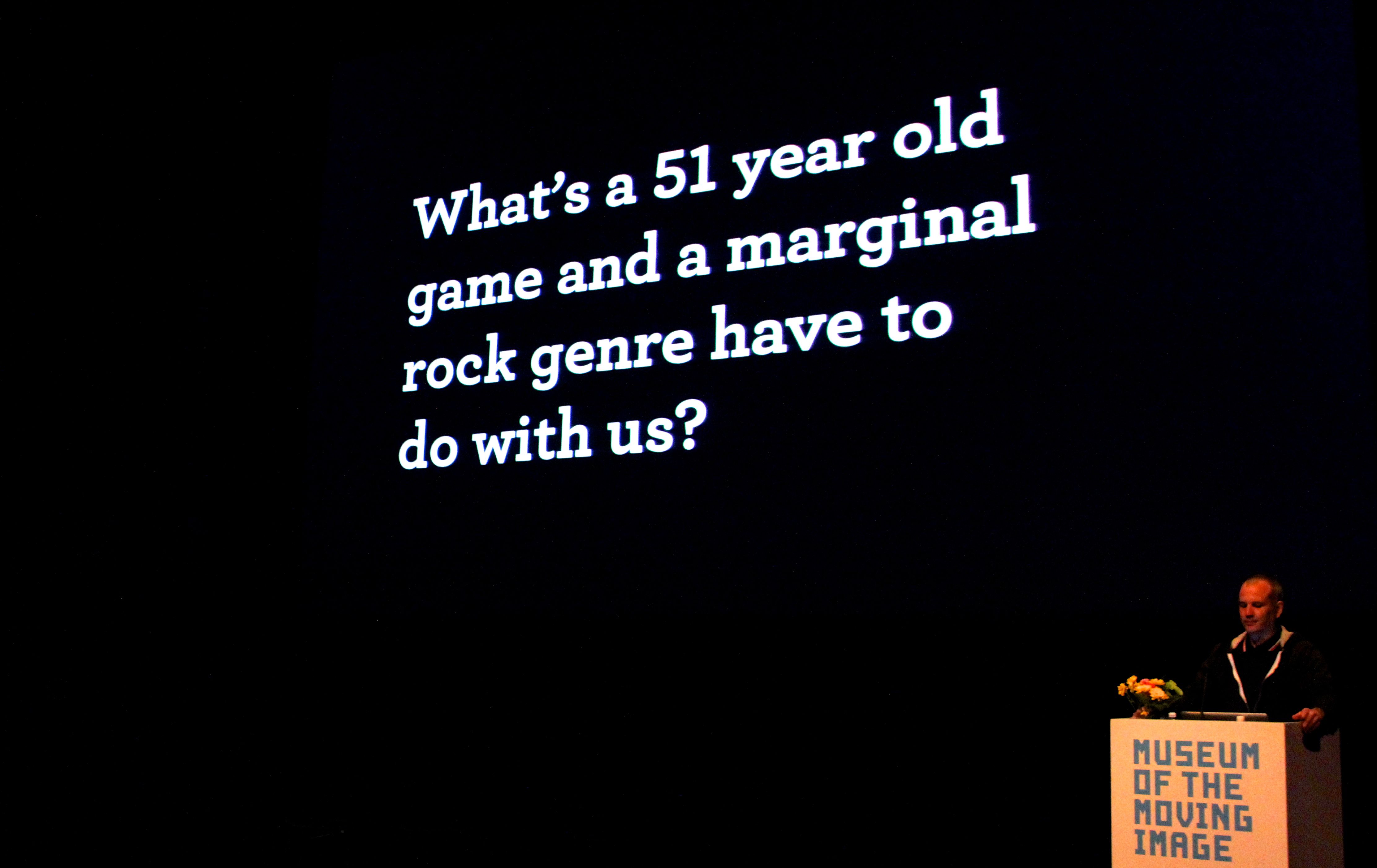

Spacewar!, Punk Rock, the Indie Dev Scene and John Sharp

At this year’s IndieCade East, Associate Professor of Games and Learning at Parsons and co-director of PETLab, John Sharp, gave a fascinating keynote speech entitled, “Spacewar! Punk Rock and the Indie Dev Scene: A Semi-Secret Quasi-History of Our DIY Roots.” In addition to sparking discussion amongst the crowd (and tweets like: My conclusion after @jofsharp’s talk – Indie games needs queercore and riot grrrl, like seriously), the talk sparked our curiosity about John Sharp’s DIY punk roots and how they play into his work here at Parsons–inspiring the interview below.

Enjoy…and be sure to catch up with Sharp, and his PETLab and Local No. 12 partner-in-games, Colleen Macklin, at the upcoming Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, March 25th-29th. They’ll be presenting: Play, Make, Appreciate: A Games Education Manifesto on March 25th at 10am.

AMT: You mentioned racking up three art history degrees before realizing that you are “not an artist,” you’re a designer. Since we so often hear the terms used interchangeably and across all programs here at Parsons. What is the difference between the terms, as you see it?

John Sharp: I actually realized pretty quickly into the first degree that I wasn’t an artist. It had a lot to do with the kinds of work I was making, the places and people for which I made it, and how I thought about the work. I wasn’t really interested in exhibiting in a gallery, I was interested in being part of a community—in particular, the music scene in Athens, Georgia during the mid-1980s.

In terms of the difference between art and design, I think about them both historically and from today’s perceptions. For me, design is about problem solving, making things that serve a purpose. That purpose could be entertaining, providing shelter, serving a particular need, etc. Art then is work that explores and provokes and questions.

AMT: Among other roles in the punk community you grew up in, you made zines. Did you make these independently or collectively with friends? Did your approach to making zines at all factor into or influence the way you design games?

JS: I made zines alone mostly, but within very specific communities. In most cases, I knew pretty much everyone that would ever read the zines, so I had a certain group in mind when writing, designing and producing them. There was a format that we all favored—a single sheet of 8 1/2″ by 11″ paper folded into quarters, yielding eight small pages. So the community didn’t actively participate in the creation, but we had an ongoing meta-dialog about format and content within the community of practice.

Game design works in similar ways for me. The conference games Local No. 12 (my collaboration with Colleen Macklin and Eric Zimmerman) has designed are all part of a larger discourse on the design of large-scale, multiplayer games designed for certain contexts. We always look at other conference games that we think work for clues, and we talk with the designers of these games to better understand their intentions, the issues they encountered, etc.

AMT: Zine culture is still out there. Are there any you read now? Any other post-post-punk iterations of punk/hardcore culture that you’re currently connected to?

JS: I don’t have any zines I make sure to read, but I always pick them up when I encounter them. The culture has changed so much over the last 25 years, particularly around how they are produced, the form they take, and how they are distributed, but there is still a lot that stays the same with the attitude, the DIY spirit, and the often deeply personal expression that they embody.

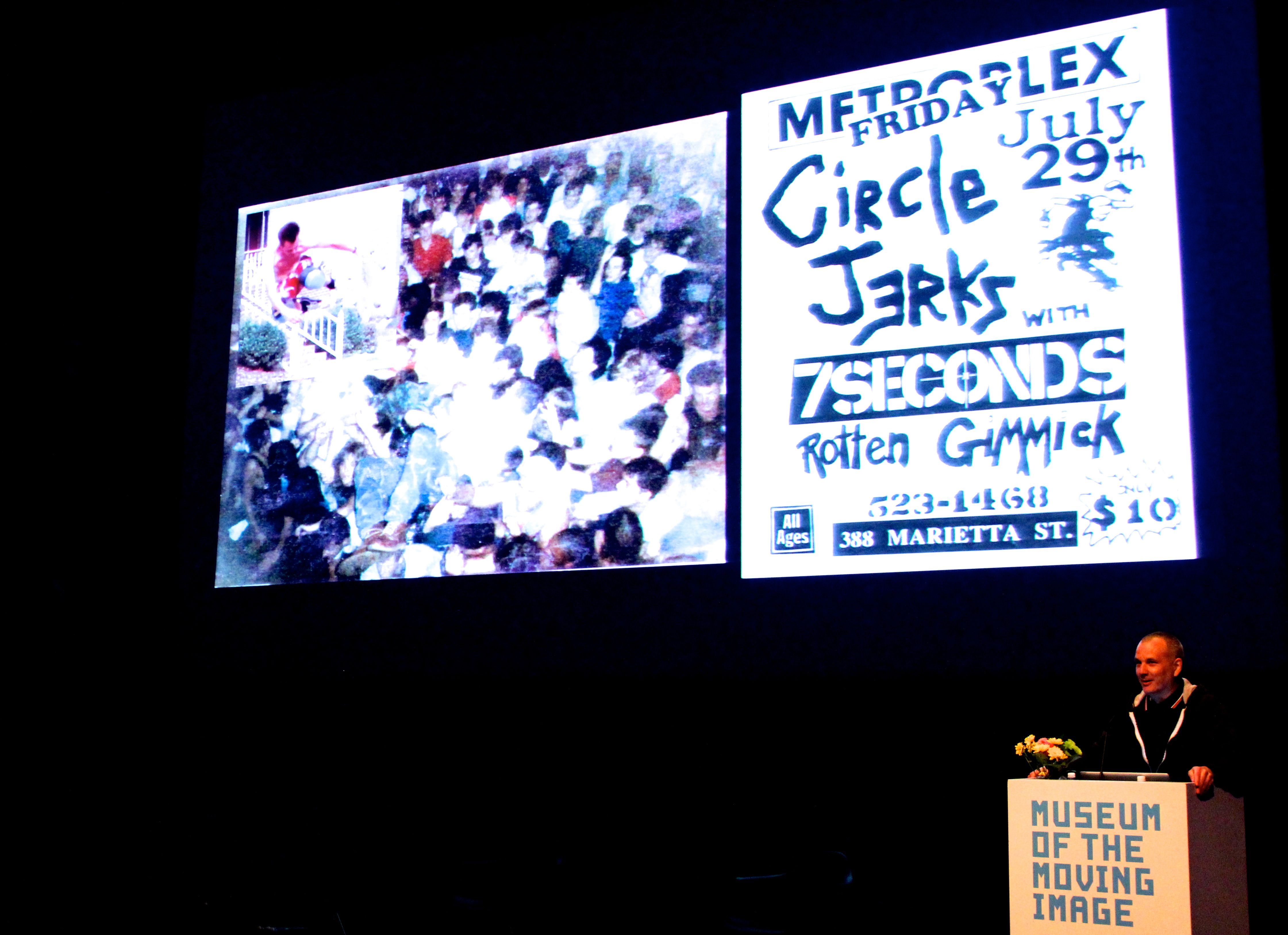

I still keep up with bits and pieces of hardcore and post-punk. I’m a huge fan of the Toronto hardcore scene and bands like Career Suicide and Fucked Up. They carry on the spirit of hardcore while still making it feel alive and part of the contemporary world. I also love that folks from the early days of hardcore like Keith Morris, once in seminal bands like Black Flag and the Circle Jerks, and now fronting Off!. Mostly, though, I’m connected to the values and ethos of hardcore, and the DIY spirit.

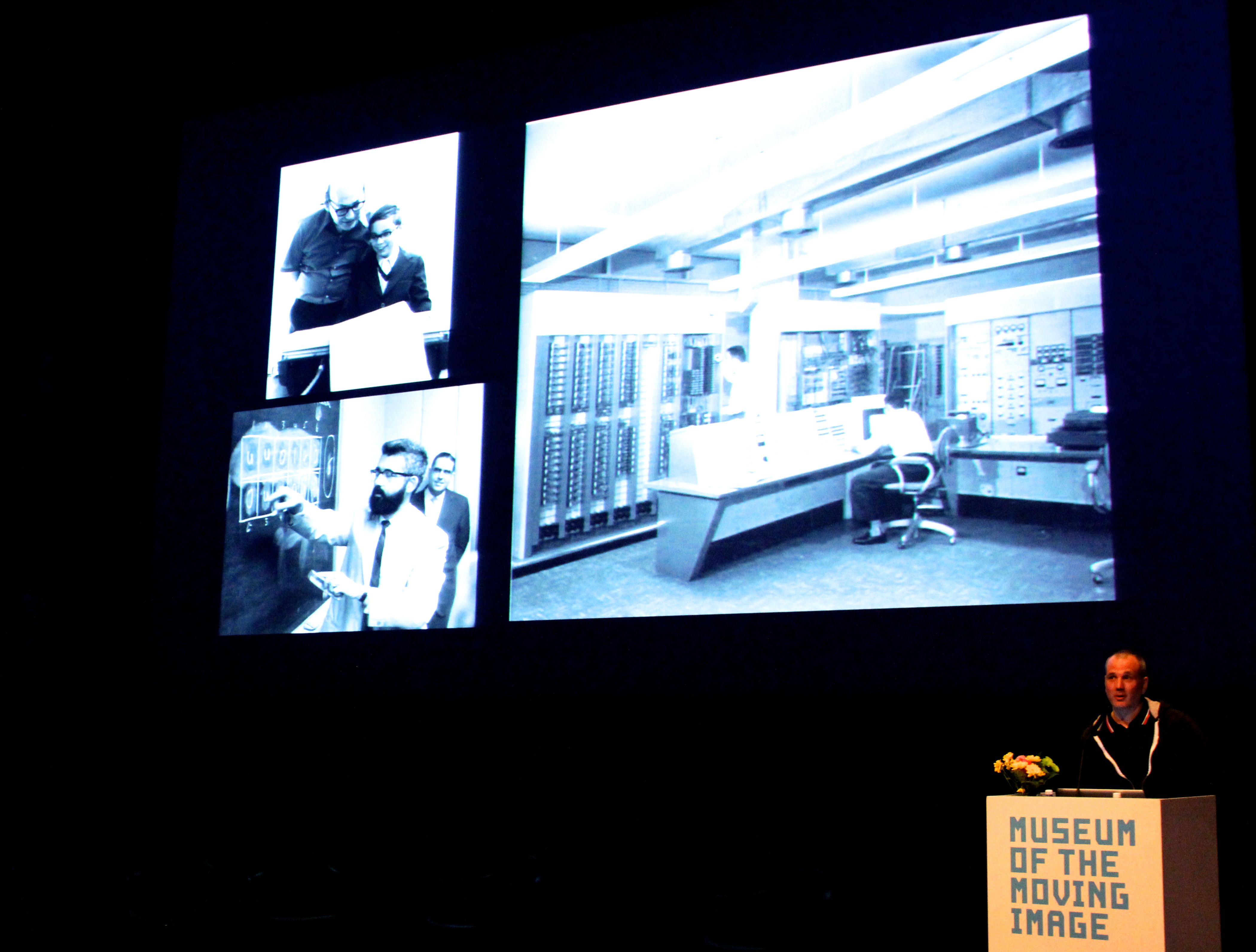

AMT: In your talk, you said that both punk rock and game design “filled the void by making.” The void for those early pioneers and fans of punk, arguably from the time of The Sex Pistols through the American hardcore scene in the nineties, was a lack of any alternative to canned, commercial pop and conservative, capitalist ways of living and thinking. For the pioneers of game design, the MIT research group who tinkered their way into creating Spacewar!, the void came out of the fact that fun, shared ways of playing with up-and-coming technologies just didn’t exist. So what void did punk, and later, game design, fill for you personally?

JS: Punk rock and the communities around it provided a place for me to feel at home. I already felt much of the disenfranchisement and dissatisfaction associated with punk, but I didn’t realize there were others that felt the same way. So punk gave me a community within which my feelings and opinions were embraced. Once in the community, I discovered that I could contribute in ways beyond music, something outside my skill sets. So I began designing t-shirts, taking photos of shows, making mix tapes for my friends, and a little later, radio DJing, making posters, etc. I found my voice as a designer within the DIY spirit of hardcore punk.

I was five when Pong was released, and 10 when the Atari VCS came out, so videogames were part of my life from early on. But it wasn’t until I was teaching at Parsons in the early years of the MFADT program that I began to think about making games. I was working as a creative director at an interactive agency where we were making websites and games, and was teaching studios with a focus on interaction design. I began to use games as exercises for teaching interaction design principles, and quickly began to see games as the most interesting form of interaction design going on at the time. I was attracted to designing interactions as an aesthetic experience. Over the last eight years, I’ve increasingly focused on games as the things I’m making and studying.

A game of Armada D6 (unpublished board game developed by John Sharp and Eric Zimmerman) in action at IndieCade East!

AMT: Another thing you said during your talk, was that the indie game design scene has started to look like the Junior Businessmen’s League, and that you’d like to see more anger being expressed. Can you explain what you mean by that?

JS: These are really two separate things. By Junior Businessmen’s League, I mean that some folks involved in the indie game scene are more focused on what I view as business-related tasks like marketing, getting in front of players, the economics of the various platforms, etc. While these are worth understanding and doing well, they sometimes distract from making a broader range of games that aren’t just part of the mainstream. Most everyone in the indie game scene that I know got into it because they wanted something different than what the mainstream industry creates, but too often, people lose sight of that and they begin reproducing the infrastructures and focuses that lead to run-of-the-mill game products.

With my wish for more anger in games, I mean I wish more were not taking the status quo for granted with games. I want us to question more, to see what is wrong, unfair, mundane and try to do better.

AMT: How is your work expressing anger or addressing the need for diversity in the game design community (aka, the question of where are the game design versions of riot grrls and queercore kids?)

JS: I guess I am supporting and funneling anger in a variety of ways. The work I do with conference organization is more about supporting diverse voices and giving them a place to be heard. So I’m not exactly expressing my own anger so much as giving others a place to express theirs. With the game- and play-related projects we do at PETLab, the anger takes the form of looking for ways for games to be part of conversations and communities that are trying to effect change. Our collaborations with the American Red Cross and the Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre for example—we are looking to find ways to help at-risk populations deal with climate change, and to help Red Cross volunteers better do their jobs. Or our Art Play curriculum that we’re working on thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts—we are developing K-12 curriculum to integrate games into arts classes so that we can bring new voices into the creation of games.

The games Local No. 12 create are looking for unexpected places in culture and communities to playfully insert games. So this isn’t necessarily about anger, but about looking at the role of games in a slightly different way. Take the Metagame Culture Edition as an example. Most anyone with a love of film, or music, or art, or games find themselves engaged in conversations about what makes one work more or less interesting than another. So we adapted the card game we created around videogames to work with a wider range of culture to both make this sort of ad hoc debating about aesthetics into something more playful.

AMT: What else can be done to help “stealthily bring more people into games who come to Parsons for other things,” as you put it. What are some of the reasons you’ve heard from students about why they’ve switched concentrations and opened up to games?

JS: It is true that MFADT is often a place that people find games. Most people are only exposed to games involving space marines or soldiers shooting things, elves casting spells and other typical game tropes. So it isn’t a surprise that they think games aren’t for them. Colleen, Kyle, Nick, Robert, Ben and I (the folks currently teaching game-related courses in the program) try to show the power of games to the students who might have opinions formed by mainstream games. We have expose them to more diverse kind of games, we show them the power of designed play, and we give them opportunities to make all sorts of games and toys.

AMT: To the point above, you said that having a computer science degree usually hurts your ability to make interesting games (sorry for the paraphrase!) This seems to be a message that needs to be blared from the rooftops in order to bring in more “creatives” who assume they can’t make games. Where would you suggest that the tentative game designer go to learn more about making games?

JS: Places like AMT, and our peer programs at ETC, USC, NYU and the like are the right kind of mix and balance to show that there is a place for more people making games. Colleen and I are giving a talk on this subject at the upcoming Game Developers Conference, and again in slightly different form at the Different Games conference here in New York. But where Colleen and I are hoping to have an impact is well before people get to college. We’re already created a couple of different curricula for young people, and we’re hard at work on our third, Art Play. We want games to be part of arts education in K-12 programs. If we can get more young people thinking about and making games within an arts context, as opposed to an engineering context, then I think we’ll see more games that speak to more people.

AMT: Have you thought of merging your two loves into an epic board game battle between, say…straight edgers and gutter punks? Anarchy D6?

JS: You know, I haven’t really spent much time thinking about merging the two worlds, but it is definitely a good idea.

AMT: Reeling it awkwardly back home to Parsons, what projects/courses/upcoming events are you currently excited about?

JS: There is a lot going on these days. Colleen, Heather Chaplin and I just got back from SxSW where we did a lot of talking about our Data Toys project for the first time, including our exciting partnerships with Radiolab and Public Radio International. Local No. 12 has two games in progress that will both be launching in the Fall—Losswords, a word game that uses rights-free literature as its play field, and a reboot of the Metagame. I also have a book coming out in the Fall through MIT Press— Works of Games, which looks at the ways games have been used within and outside the artworld to create art. And I’m helping run a couple of conferences this coming Fall—the Digital Games Research Association conference in Atlanta, Georgia in late August, and IndieCade in Los Angeles in early October. It is going to be a crazy, fun year.

AMT: Sounds like it! Thanks John.