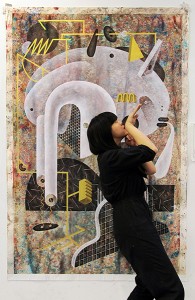

In 2014, for the second time, China’s foremost state-run institution of contemporary art – Power Station of Art – hosts the Shanghai Biennale, in its converted power plant space.

In 2014, for the second time, China’s foremost state-run institution of contemporary art – Power Station of Art – hosts the Shanghai Biennale, in its converted power plant space.

Entitled “Social Factory”, the 10th Biennale asks what characterizes the production of the social, and how “social facts” are constituted. A recurring point of reference is the year 1978, acknowledged as a turning point in the recent history of modernity. 1978 was also the year in which Deng Xiaoping, who was to become China’s most influential Leader in the following decades, initiated his landmark socio-economic Reform and Opening, re-invoking Mao Zedong’s 1938 exhortation to “seek truth from facts”– a practice that sought to separate accounts of objective reality from subjective imagination. “Social Factory” contrasts this principle with the call to use fiction as a means of social reform, made by earlier seminal Chinese modernizers, like scholar and journalist Liang Qichao, and China’s seminal social critic and writer Lu Xun, who wrote The Story of Ah Q, Diary of a Madman, among others.

In this vein, the Biennale explores an interlocking set of questions: What is the relationship between the social and the fictive in the construction and re-construction of society? How has the production of the social changed throughout 20th century modernity? Has the production of the social entered a new phase with the massive influx of “sociometric” technologies, the extraction of data and digital profiling, and the increasing automatization of social processes in algorithms? And does China’s pre-modern history of social systematization through unparalleled bureaucratic machinery and archiving capabilities echo in the country’s current processes of social fabrication? How can we grasp the simultaneous impact of history and that of technology on subjectification today? And how does the general process of acceleration and diversification of subjectification play out in the case of China and its current era of social reconstruction?

The “social” is produced by developing the human capacity to relate, through care, affection and education. The process encompasses the creation of symbols, abstract images and conceptual generalizations, which goes hand in hand with the formation of institutions and material culture. It also includes the constitution of a particular economy of signs, their “animated” and ambiguous relations to functions, meanings and things. Due to this complex genealogy, “social facts” can never be entirely known; they remain partially implicit, situated between the actual and the potential.

In modernity, this ambiguity of the social, and the possibility to plan and engineer society that hinges on it, has been a matter of ongoing contestation. Bureaucratic procedures, surveys, statistics, and concepts of identity have variously sought to reduce the complexity of the “social hieroglyph” (James C. Scott), in order to separate the meaningful from the meaningless or legible “signals” from “noise”. Drawing on both contemporary and historical works, as well as music and cinema, the 10th Shanghai Biennale presents art works that call such separation, and its historical productivity, into question.

November 23, 2014 – March 31, 2015