Second Nature

Chelsea Haines

Each spring, the blossoms of the cherry tree mark what appears to be the eternal renewal of the seasons, a sign of the natural order of things. Yet a cherry tree is never just a cherry tree. As Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels point out in The German Ideology (1846), the cherry tree of the Euro-American imagination is far from an eternal given. Speaking out against the German idealists of their time who tried to claim the “sensuous certainty” of nature—that is, nature’s innate and unchanging essence beyond time, space, or human mediation—Marx and Engels argued that the cherry tree is a relatively recent agricultural export from western Asia; it is a product of history, society, and commerce.

This nineteenth century debate over a cherry tree illuminates what we might consider today as the paradoxical ‘nature’ of nature. Nature itself is a historical, man-made category. To speak about nature, then, we are already speaking about a kind of second nature, a world refracted through human perception and intervention.

The exhibition Second Nature offers new artistic interventions and observations of a fragile world: a world in which social relations are masked by ahistorical, untruthful ‘truths’ brandished by a rising global tide of right-wing extremism without regard to context or reason; a world in which technics and ideology have merged to produce a complex image-landscape in which reality can no longer be taken for granted; a world in which nature has been altered so quickly and completely as to become almost a simulacrum of itself. In this uncertain and challenging moment, this diverse group of artists, informed by their shared experiences and working proximity over the last two years, are developing methods to critique, analyze, and recover vulnerable images, materials, and relations. Together and separately, their working processes have become another kind of second nature—an almost instinctual critical approach to looking at and making images—formed in the intensive learning and working environment of the Parsons Fine Arts MFA Program.

The phrase second nature is most frequently used to describe an act or habit that is practiced so often that its execution becomes almost effortless. Second nature may imply a high level of mastery of technique. Lucas Pérez has pursued an intense examination of the process of mastery over the last seven years as he trained to become a shihan (master-teacher) in the Shosenbu Calligraphy group in Nagoya, Japan. After achieving the highest level of technical mastery possible, Pérez set about its undoing. In the video Throwing away eight years of calligraphy (2017), the artist dumps his practice sheets down the trash shoot of his apartment building, thus destroying the material traces of his training. The video accompanies a large silver Japanese folding screen marked with his newly un-mastered ‘perfect/imperfect’ gesture.

The tension between skilling and deskilling is also central to Robert Panichpakdee’s practice. Through painting, sculpture, installation, and performance, Panichpakdee, a self-proclaimed trickster, questions the nature of the completed work, and its value and position within the art world. For this exhibition, he has destroyed a series of paintings, and will instead display photo reproductions and burnt remains. As in all the artist’s work, this series interrogates and undermines the status of the auratic art object in both the art market and museum world.

While some artists in Second Nature interrogate notions of practice through cycles of concerted effort and destruction, others work towards the careful preservation of objects. Shenyuan Ke’s sculptural installations subtly address the social impact of China’s One-Child Policy (1979–2015) through her own childhood toys and stuffed animals. These childhood objects are treated with exceptional, almost overbearing, care. Wrapped in yarn, they are both protected and confined, alluding both to the traditional Chinese practice of foot binding for young girls and the overprotective stance of many Chinese parents towards their only children. Her installations speak both to the ways in which girls are treated in China as precious objects and to the objects themselves as surrogates for siblings that could not exist.

Gregory Simoncic’s ongoing series, Transfixed (begun 2017), similarly borders on the autobiographical. Simoncic takes the most intimate of his used, everyday items—such as lipstick, nail polish, ear buds, anal bleach, or condoms—and places them in a honey mixture, which are then vacuum sealed in FoodSaver bags and displayed together as constellations in larger sculptural installations. Through his process and display mechanisms, Simoncic plays with both the apparent neutrality of scientific observation and the cold allure of commodity fetishism. However, on closer inspection he reveals the ways in which these objects have been ‘used,’ or irreversibly touched, marred, and otherwise transformed by the human body.

The physical memory of material is central to the work of Daniel Llaría. In his sculptures and videos, Llaría evokes both questions of identity—sexual, class, national, generational— and connections, resonances, or tensions between seemingly disparate groups. For this exhibition, Llaría has produced an installation made from the seams of workers’ overalls and nylon straps, which in turn hold up objects cast in concrete. Part of the series titled The Get-Rich (2017), the installation forces a confrontation between two different kinds of work, namely manual labor and artistic practice, as well as their differential economic and cultural values.

Through her multifaceted practice, which includes sculpture, photography, video, performance, and installation, Haleigh Nickerson investigates the complexities underscoring the construction of black female identity. In her installations, she has developed strategies of sensorial overabundance, assembling materials, objects, and images from a range of archetypal and iconographic sources, including series of video and photo self-portraits in which the artist represents herself through several historical and fictional characters. Taken together, Nickerson’s installations tap into the constantly shifting relationship between beauty, power, and self-representation.

Katie Chambers’ works move between painting, sculpture and textile in order to complicate the social, economic and personal meanings of clothing. Chambers disassembles previously worn clothing and accessories and reassembles them into objects that exist between painting and sculpture. Clothing is often considered a second skin that shields our bodies from the world around us. Through her layered interventions, Chambers denaturalizes clothing and offers new ways of seeing them as harbingers of memory and meaning.

Moments of vulnerability, intimacy, and reflection inform the work of several artists in Second Nature. Mihika Shah explores materiality at the moment just before its disintegration. In Forever (2017), Shah has hand produced hundreds of delicate shells made from black paper pulp. Both the time and careful handling involved in producing these shells as well as their fragility serve as metaphors for the human body, our vulnerability, and inevitable decline. Shah’s work strikes a balance between creation, maintenance, and loss of control as well as the boundary between material form and its undoing.

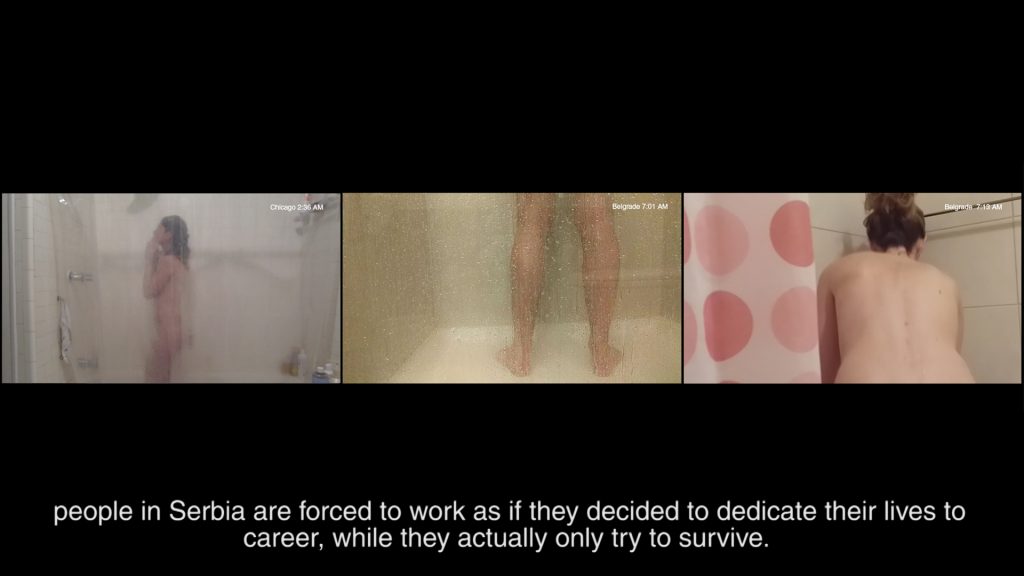

Marija Marković’s video installation in the exhibition explores the meaning of the Serbian word dokolica, a largely untranslatable word that roughly corresponds to English ideas of “free time” or “non-work.” Marković asked sixteen friends to speak about the meaning of the word during their one remaining moment of dokolica during the day; as they shower. Their reflections on the current and past meanings of the word highlight the economic and social transformation of Serbia, and the increasingly blurry boundaries between free and working time under global capitalism.

Hillary Wagner’s work explores the complexities of memory through images and materials recovered from her grandparents’ now-abandoned dairy farm in southwestern Ohio. In the exhibition, Wagner has produced an installation that effectively recreates an image from her childhood in the physical form of a steel tank used for keeping milk fresh before pasteurization. The steel tank, with its swirling milk, is paired with found drawings and documents from her grandparents and Wagner’s poetic responses to them. Together these elements recall not only a specific place and moment in time, but also the attempt to recover a bond between the artist and her family.

The exploration of intimacy and familial bonds are also at the heart of Francesca Fiore’s work. In the project Frail Places (2017), Fiore collaborated with her sister to investigate and unravel the relationship between two fictional sisters: Antigone and Ismene of Sophocles’ Greek tragedy Antigone. After researching and developing their own rewritten scenes of the play focused on sisterly intimacy, Fiore and her sister returned to the high school auditorium where they had once performed the original play. The resulting poem and installation, rather than a finished narrative, reveals the story of a process, which sits on the border between fiction and autobiography.

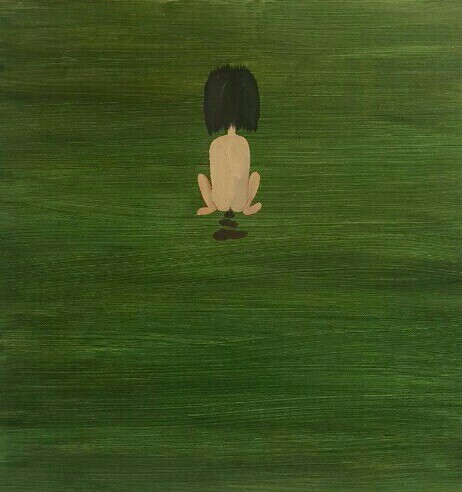

Yeu Ryang Choi’s painting series, Homage to My Grandfather (begun 2016) addresses her memories of her grandfather, who after escaping from the communist regime in North Korea, spent his adult life in South Korea, unable to return to his family and hometown of Pyongyang. Choi provides insight into his story through her own personal recollections. In three new paintings, titled The Memory with My Grandfather (2017), Choi isolates three specific yet seemingly unexceptional moments: ironing her grandfather’s handkerchief; watching him play a Korean card game with friends; and waking him up to have breakfast together.

The memory of places where one can never fully return anchors Luma Jasim’s diverse practice, which has been informed by her personal experiences as an Iraqi refugee now living in the United States. For this exhibition, Jasim is displaying work from Long Term Vision (2017), a series of large paintings overlaid with video projections. Through the conflation of these two media, Jasim produces a single formally and politically poignant image in which an animated figure almost, but never entirely, breaches the borders of the painting’s picture plane.

The phrase second nature implies a practice that is first learned, and later, internalized. Several artists in this exhibition act to alienate and undo social categories that have become central to our perception of others and ourselves. In her videos and installations, Lydia Nobles examines relationships between human and non-human animals through performances, interactions, and filming of her dog, Remi. In these projects, she works through what love, sensuality, and the erotic could look like outside the confines of normative social relationships and hierarchies. In her statement in this catalogue, Nobles writes about her work as a process of defamiliarization. This defamiliarization often takes the form of challenging and sometimes uncomfortable categorical slippages: human and animal, physical and psychic, image and material.

Defamiliarization, or estrangement, is also central to the work of catherine fenton bernath (cfb). While cfb’s practice is grounded in self-portraiture, the resulting photographs and installations undermine naturalized conceptions of the self as a fixed and autonomous subject. In fact, her work points to the ways in which the body and gender can be understood as the result of multiple and contradictory social forces and norms. Her work stresses fragmented and contingent conceptions of the self through her formal techniques of piecing together and suturing her assemblage works.

Some artists in Second Nature pursue strategies of defamiliarization to analyze how technological developments shape human perception. Cali D. Kurlan’s work investigates the inherent optics of the camera. She combines digital and analogue technologies to produce photographic prints that highlight both the photograph’s material status as well as the process of its technological production susceptible to manipulation, transmission, and circulation across multiple platforms. These photographs often double as props or backdrops in her installations, which play with the standards of exhibition display in the white cube gallery.

Daria Zhestyreva similarly plays with the boundaries between digital and analogue practices in her process-based work, using computer software, such as CGI, to produce her sculptures and paintings. For Zhestyreva, machine optics reveal different states of the conscious and unconscious mind. Through technological apparatuses, she questions the stability of reality as perceived through vision. For this exhibition, Zhestyreva displays both a physical painting made through a software program and a virtual reality headset that reveals the digital process through which the analogue painting was produced.

Some artists in Second Nature take everyday environments as their subject matter and abstract them, pointing to the strange and even oppressive landscapes of what appears, at first glance, to be entirely ‘natural,’ or commonplace. Sun Yue, for example, takes as her starting point a chair. Isolating this everyday item, and removing it from its context as a function, backdrop or otherwise socially useful object, she abstracts and flattens it through digital renderings into disassembled parts of a whole, which cannot quite be reassembled into the original. In reimagining the object’s status, Yue experiments with translating image into sound, further erasing its material traces and objective unity.

Bridget Moreen Leslie expands on the deconstruction of the everyday through an investigation of “non-spaces”: often institutionally undefined architectural containers, such as corridors, lobbies, bus stations, and airport terminals. Leslie makes sound recordings of these non-spaces, which are later altered and accentuated based on differences in sound frequency within the same space. For this exhibition, Leslie has produced an installation pairing these sound recordings and videos of non-spaces with a bench commonly found in airports as well as architectural renderings of so-called pure sites, sites without context or history.

Justin Sterling’s assisted readymades illuminate how the urban environment shapes and controls social behavior. In Stuck (2017), for example, Sterling intertwines two window grates commonly found on the exterior of windows in New York’s “high crime” neighborhoods. As the window bars keep intruders out, they also perpetuate feelings of fear and threats through their very design and implementation. Sterling’s sculptures remind viewers of the widespread yet often invisible forms of institutionalized violence and incarceration.

Unconscious and subconscious desires are the subject of Xin Liu’s paintings, which incorporate the signs and slogans of advertising and the mass media into dreamy abstract compositions. By appropriating the symbols of luxury and leisure portrayed in popular advertisements and isolating their most intimate and sensual elements, Liu heightens awareness of the sensuality for sale in our image landscape. Ultimately, however, his practice moves beyond appropriation to elicit provocative questions about how painting itself may act simultaneously as both advertisement and commodity.

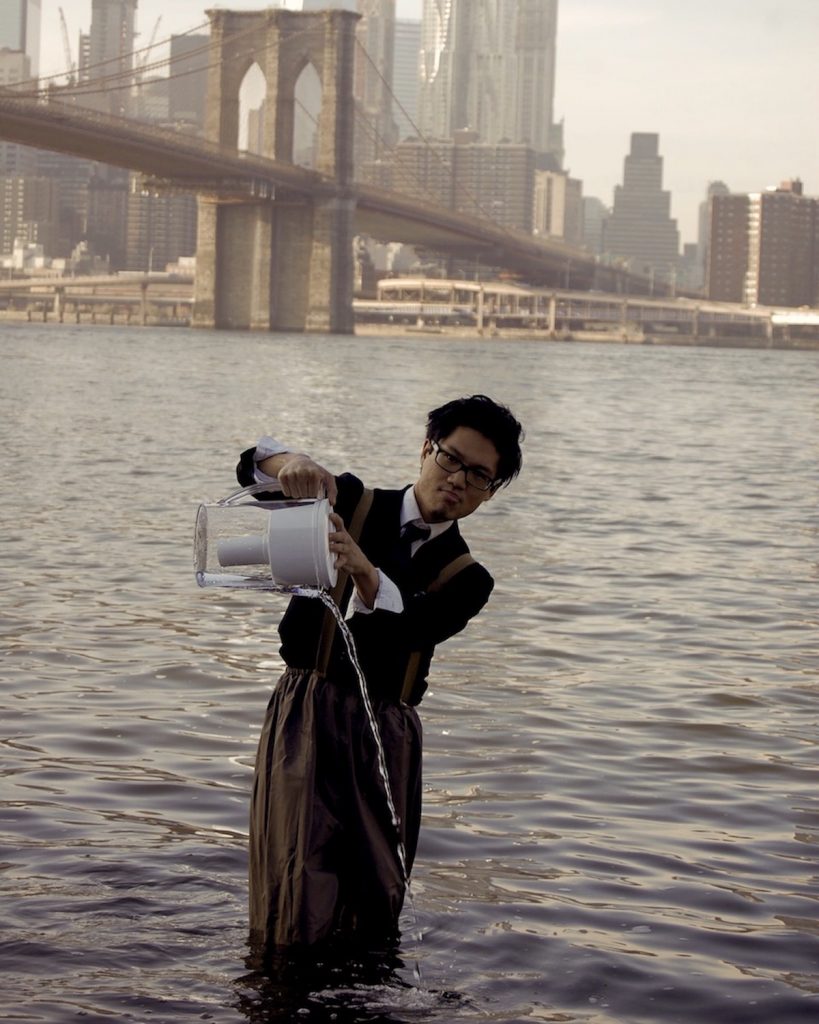

James Hsieh further explores the world of dreams in his sculptures, video installations, and performances. Hsieh creates vibrantly otherworldly landscapes and creatures, eliciting memories of beings often associated with childhood dreams. Importantly, in his performances and video installations, the subject—whether the artist himself as performer, or the visitor to the exhibition—remains alone. Solitude is central to Hsieh’s work, which despite its vibrancy, is framed within an isolated dreamscape in which communication is just out of reach.

We are aware by now that the new state of exception we are about to enter is no longer an exception at all, but the rule. Second Nature is both a commentary on the serious challenges of our present and a proposition for ways of working around the new status quo, exploring how this group of artists mediate the world around them, and in turn, create new worlds for themselves.