Interview by David Chan, BFA ’16 www.davidchanstudio.us is an artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Interests include modern art, structural film, consciousness, and the human condition.

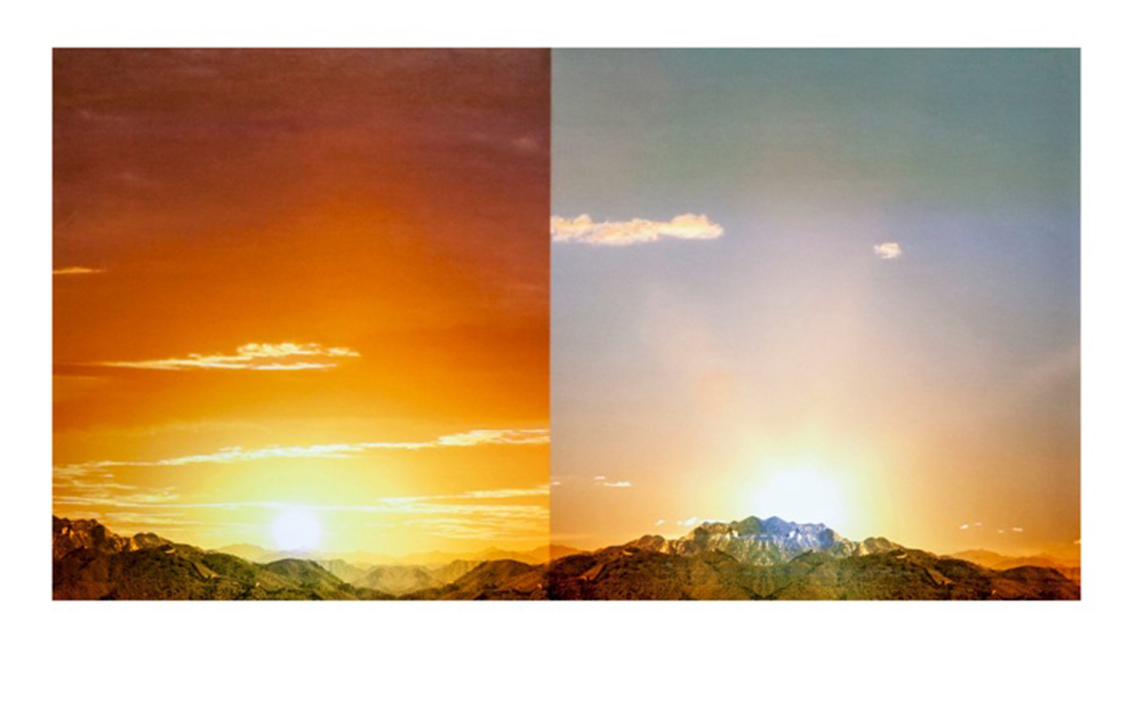

Magali Duzant is an artist based in New York City whose work deals with themes of time, the collapse and tracking of it, the documentation and visualization of the non-physical, and the condition of searching but not knowing what for. In her project Sympathetic Magic, Duzant focuses on using photography as a tool to feed the desire for spirituality and to define something the metaphysical in using different objects, but most notably a year-long collection of aura photographs. In Live Streaming Sunset, she captures sunsets in all 4 different time zones across the United States and projects them continuously in a window in New York City. I sat down with Magali to talk about her beginnings, and how she functions and works as an artist today in New York City, and how the themes of our work relate, being that our work is in conversation and has many overlaps. In my work, I find myself also trying to define something that is extremely abstract and difficult to immediately visualize. We discuss the challenges of making this type of work in depth. I also talked to her about life after grad school, and how it is to live and work as an artist while still making money, which led to a lot of great advice for young artists out there.

David Chan: Hi Magali. I would love to start by talking a little bit about your background- where you grew up, where you did your undergrad, etc.

Magali Duzant: I’m actually from New York. I grew up in Queens and went to high school in Manhattan. I went to an arts high school- LaGuardia (Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School). The “Fame” school – dancing on taxis and shit. My mother’s family has lived in New York for ages and my dad is from the Caribbean—French is his first language and he is adorable. My dad is short and my mother is really tall, so they are like the odd couple.

DC: This explains your last name and your first name, which I’ve always wondered about!

MD: Yeah, Magali Duzant. It sounds fancy, I feel like I have a destiny to grow into it or something. I was really lucky when I went to high school because we took art courses every day. When I was applying to my undergrad, I was thinking I would either apply to art school or to a humanities program and study something like International Relations. I ended up doing both somewhat. I went to Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, and I hated it when I first got there.

DC: You hated the city or the course?

MD: I hated the city, and I wasn’t sure about the course. I ended up loving it, and I did a double major in fine art and anthropology. I technically minored in photography but they wouldn’t let me make photography my main concentration because they didn’t have enough students in the program. While I was doing that, I worked as a production assistant and that’s where I really learned all of my technical skills. I don’t think I picked any of it up in classes the way I did hands on.

DC: Was that on film sets or photo sets?

MD: Both. I think a lot of my work comes out of the fact that I have self-taught myself a lot, and that I’ve done a lot of different things. I worked for a commercial photographer who did huge national ad campaigns, and I did all of his talent scouting and location scouting. I also worked for a photographer who did all interiors, which was a nice thing because we would travel to people’s mansions and shoot for Architectural Digest. I graduated straight into the recession, but I was really lucky. I had interned at a small photo gallery while I was in school, and right as I had graduated, the director was asked to fill the position of curator of photography at the Carnegie Museum and I was first asked to take over to take over installation within a week of graduating. Later, I interviewed for the job of exhibition coordinator and got it, which was amazing and scary, because I just stretched the truth the entire interview. I pretty much

just told them that I had all these skills that I didn’t. And I just sat down and had a complete panic attack, and then just started to teach myself all of these things.

DC: So you learned how to work and function in a gallery, which you never really experienced before?

MD: Yes, it was great because I learned a lot. I learned that I never want to work for a gallery ever again. I learned that working in non-profit was rewarding and incredibly frustrating. After about a year, I decided I wanted to leave Pittsburgh. I applied for a residency in California; I had gone to San Francisco and loved it. I got the residency but I had three months, and so I saved up enough money to travel, and I traveled across the country— I went down to Baja, I traveled up the west coast, took the train across Canada, I came back to New York, went up to Montreal. It was just this amazing time where I thought about work and spent money.

DC: Money well spent, though!

MD: I looked at my savings account, and I thought, “Well, it’s always good to start fresh.” I spent the next two years in California in San Francisco and I was an artist-in-residence at the Kala Art Institute. It was a really amazing space in Berkeley specifically for photographers, printmakers and video artists. I took the time to figure out what I needed to do, and at some point I realized that I was interested in maybe teaching, and it was something that I wanted to continue to do. And that’s when I decided that I wanted to do a graduate program. I knew I wanted a photo program, but I wanted one that was open and I really wanted to be back in New York, so I applied to a number of schools and was deciding between ICP-Bard, SVA, and Parsons. I chose Parsons for the structure of the program, scholarship ( I was determined to not take on debt ), and the connection to the New School. I ended up taking classes in the media studies program which was really great. I enjoyed finding my way to the notion of public art as something I was interested in. It’s exciting and a little overwhelming.

DC: Can you briefly define “public art”?

MD: When I think of it, I think of art that is not necessarily in a gallery space, that exist in communities outside of your typical art realm, so in the live streaming sunset piece, I showed it as part of the thesis show exhibition. But it was really facing the street, so it was available to the passers by; it was accessible to anyone walking by.

DC: So is it important to you that the work is accessible to more than just the art world and this specific crowd?

MD: Yes and specifically with this project, I am capturing a routine, and something that is available to anyone in one way or another and bridging distance. I grew up in Queens and because Queens is such a huge immigrant population I’m thinking about how great it would be to have it there, and how great it would be to bring different viewpoints into one place ( mimicking the make up of the borough ). There’s something calming and soothing about this imagery that I am seeking to bring back, but also to think about, why should something that is public in its essence be made private and specific to a community that isn’t necessarily that open, so to put it back into a public space.

DC: In the more recent work that you have made, like Sympathetic Magic or Live Streaming Sunset for example, are there themes in there that resonate with you? And how long have you been working with these themes?

MD: Time is a huge theme. The collapse of time, the tracking of time, is something that I have become interested in, has been present in a lot of my work over the past few years. I think isolating it as this topic of interest is what I see as this desire in contemporary culture to track, record, and analyze data. The idea of smartphones, social media, that “everyone is a photographer”, that everything is being recorded

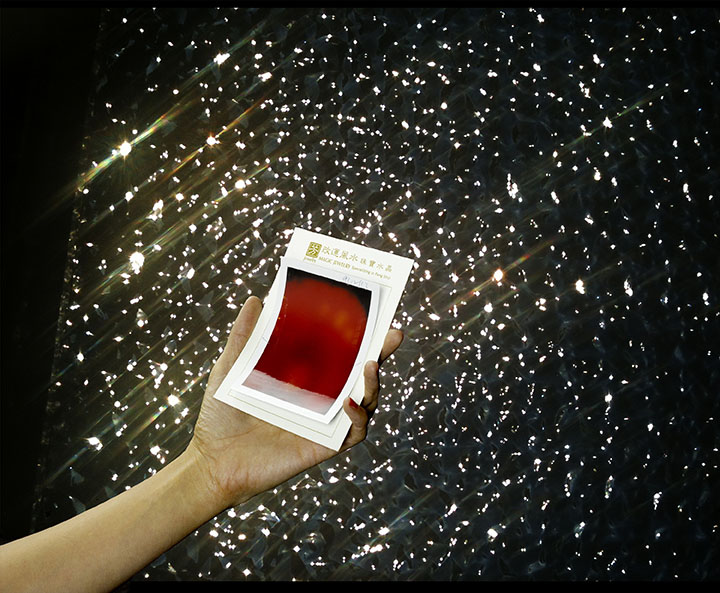

in some way, shape, or form, and trying to utilize that in my own work. But to use that to analyze things that are a little bit beyond our normal perception. I think in almost every project, it comes down to- How do we visualize something that we can’t see? How do you visualize the sun setting all over the world? How do you visualize an aura, an energy field, or a belief system? And then they kind of shoot off, because each project brings its own “something” to it, so with the auras, I ended up becoming really interested in translation, and layers of translation through interaction or the terms that we use to describe these unknowable things.

My aunt has a summer house up in the Adirondacks and she tricked me into cleaning out her storage space. It was the worst-best vacation ever. I found this box and there were maybe 40 black and white negatives from the 20’s and a two-tiered slide organizer dating from 1949 to 1970. A stranger’s family’s photos, which was very weird. At that point, I thought a lot about different kinds of archives, the index, and how that worked. The more work I made, the more I see it as this interest in time, in memory, and kind of the vagary of that. How memory is so different from reality but supersedes reality a lot.

When I started grad school, I wanted to do something different and I ended up going back to these slides and making this installation piece. I realized that what I was more interested in was the idea of projection, and really interested in the projector as a tool and as an object as well. I went back into the space and photographed the space where the slide had been taken with a projector screen in it, and I projected the original slide on to this print of this space. That was the gateway project that then led me to thinking about time and how to collapse time and distance. I was missing California a lot, which I didn’t really think I would, and I was having this feeling of dislocation and a lot of it was this urban experience. New York was always sort of pressing in, and I didn’t think it would be a big deal because I grew up here, but I realized that my surroundings on the west coast really affected the way that I thought about things. Leaving it is when I started to become interested in spirituality and the quest for that in alternative means.

DC: So, something you can’t quite put your finger on and define.

MD: Exactly. So this idea of the condition of searching. The condition of wanting more, but not exactly knowing what that is. But also thinking about the internet as this place for it, and using the internet to collapse time and space, and follow these rabbit holes.

DC: I feel like our work has a lot of parallels, in that I’m trying to capture this human experience inspired a lot by traveling on my own. Over the summer I went to Marfa on my own, and this idea of isolation became a big thing for me, and I started reading about existential isolation, and how to understand something that you can’t quite put your finger on that exists for everyone. I’ve never thought about it before this but it’s so true and it’s so overwhelmingly intense. So trying to capture something transient that you can’t define is important to me.

MD: I love the idea of continuing trying to do it. It’s like this impossibility, but there’s something there but that makes me feel like… a part of me thinks that you’ll never do it, but the other side is saying, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try, and keep doing it. And there’s something really magical about those transient moments and ephemeral experiences when you are alone and when you’re trying to make sense of something a little bit bigger.

DC: One question I had was about the idea of working as an artist. You have a lot of past experiences doing commercial work, how do you balance that with your fine art interests?

MD: It’s difficult and I think the longer I do it, the more I want to do it, but the more I also appreciate how difficult it is. I was invited back to Carnegie Mellon to speak, to do studio visits with the seniors. I was freakishly positive, and I told them I think you have to treat it like a job, you have to do the work that you actually want to do. It all sounds like throwaway advice or ideas, but it does come down to the fact that

you have to make money, so you have to make work that sells or you have to do something else that supports it and it’s different for everyone. So much of it comes down to knowing yourself, knowing how you work. I personally work part time for an artist book producer, and it doesn’t pay that well, but I do some freelance work to fill in and I teach. I’m still figuring it out and I think being open to that evolution of process and interest is incredibly important. I work my part time job because I have great benefits in the sense of having access to a 9900 printer, a studio space, and I’m working on a book project and they are helping to print. I also know that I don’t work at night, so I keep Wednesdays and Thursdays as strictly studio days, and I’m in the studio all day long and working all day. Being a full-time freelancer is not something I want to do because I feel it’s like an added stress, so to do it when it comes around, but to know that I have a job that pays my bills and my rent is great. It’s a lot about peace of mind and shaping your work life to fit your personal work life in a way.

DC: You talk a lot about the people around you and people you know. Can you talk a little bit more about the kind of company you keep and the people you surround yourself with? How do you fit into a community of artists, even if not a local one? Is it important to surround yourself with people who inspire you, people who you collaborate with and you have similar interests with, or do you have people around you who do completely different things?

MD: I am one of those people who need to have people in my life who are interested in art but are not necessarily as involved in the art world. I have two really good friends in the city – one I went to middle school with, and one I went to college with. My friend Cheryl who I went to middle school with, she has a degree in comparative literature and she works in urban design and planning. My friend Michelle, who I went to college with, we went to art school together. They are both great to go to galleries with and talk about art, but they are also outside of it. So it’s a fresh perspective. It’s important for me to have people in my life who get it but are outside of it, because it’s a small world and can be a little overwhelming. But it’s also really important for me to have a community of people I can show work to, and talk to, and who are making either similar or very different work.

Sometimes it’s really easy to look at what is trendy right now, and look at it and say, “I don’t fit there.” It’s really important to have people who reassure you, and to know that you have your own little section. I’m still in touch with people from school but it’s been really important for me to branch out and to find people who are working but are working in different media. It’s really important for me to be surrounded by people who are creative and actively making or doing, and who are interested in community and how that affects their work. It’s important to stay in touch with professors- with people who are older and working, to have a different generation’s eyes and viewpoint and world view. I try to keep in touch with people that way.

DC: I think that’s great advice to have a community outside of school. I think that’s something that I’m trying to establish for myself, and just to think about things like that in the long run. Because being in school is kind of that… but to think about it in a long term way, is important.

MD: When you’re in school, you have it, in the sense that people have to show up.You’re gonna get a grade, you have to be present, you have to show up. But I think it’s super important to seek out the people who your work is in conversation with and people whose opinions you are interested in. It doesn’t have to mean that they agree with everything, but just people whose opinion you want to know. The wider you make that group, the better it is.

DC: I think the only challenge for me is that I found it a little bit difficult to find people whose work is in conversation with mine. Maybe it’s the specific community I’m in, maybe because it’s school… there’s something about the themes that I’m exploring that is maybe not thought about by people around me. That’s why I was really inspired by your work because I felt it was the first time I saw work within the realm of school that revolves around the same kinds of ideas in my head.

MD: I think the themes you explore are themes where you are really thinking about experience in a deeper way and that’s difficult sometimes to bridge a gap. It’s not a hard theme, but it’s something that is very thoughtful. It’s difficult to show, so how do you visualize it? As far as work relating… It really takes a while. When I was at Parsons, there was this Icelandic girl Kristín who I think I’m on similar parallels with. You would like her a lot. But amongst my other classmates, I found it difficult sometimes… I could talk about my work, but I would feel like there was something that wasn’t quite coming up – people would be silent and I wasn’t sure if it was indifference or dislike. I would thank them for their advice and look at how to apply it, but a lot of times I didn’t feel like we were connecting in a certain way. And sometimes you can’t connect with everyone, some work speaks to the masses, some doesn’t.

DC: Something that I feel is kind of a big challenge with my work is dealing with very abstract themes. In critiques, I’ve gotten the comment where people say it’s really hard for them to have something to grab on to in the work because the themes and the work are really abstract. But in the same vein, I never want to be too literal. Do you feel like you have the same challenges? Because you deal with pretty abstract themes yourself.

MD: Yeah, I find there’s always a fear of being too literal. For the aura project, I was really interested in the back and forth, but also in why I was interested in it. I was interested in figuring out why I was interested, and again the idea of not being able to place your finger on it, but wanting to figure it out. When I was making photographs, I didn’t know what to do because I’m interested in the thought process and all of this bizarre history that goes with it, but in the physical objects. I was working in the studio, and I found it was so easy to fall into these literal ideas. So I started making the video piece. I started mixing in all this new stuff, and it didn’t make sense. People kept telling me, “I don’t know what you are trying to say, and I don’t know what is happening.” And I finally just realized that for me, that was okay. Because that’s what it was. I think I finally got to the point where it was okay because I don’t think I’m making work where I’m hoping the audience is saying, “Oh, I see A+B=C. Great.” It is about being abstract and maybe losing yourself in something. If people have this issue where they can’t find something to grab on to, I think it’s okay. There’s so much work out there that you get immediately. I’d rather be making work that doesn’t reveal itself immediately. People want to be able to define your project immediately, and there’s a lot of one-note work out there. There’s nothing wrong with that— I have done some projects that are like that, and exist in a certain place in space.

DC: I love the idea of the inspiration coming from you trying to figure out something that you’re not sure you can figure out. And replicating that experience for the viewer.

MD: That’s exactly it. It’s saying, “I’m trying to record and show you this process. And this process is still ongoing, and doesn’t have an end.” I think, at least in school, when people say they don’t know what you are trying to do, that’s such a thing to say in a critique when you don’t know what to say and you can’t figure the work out.

DC: In a lot of ways I feel like it’s better to have a project that you can’t ever finish ever, that is ongoing, because it’s more interesting. It’s representative of this lifelong search.

MD: Some of the themes that we are both talking about – why would you be making work if you could tie it up in a nice little package and say, this is what it is?

DC: Exactly, if it had already been figured out, we wouldn’t even be talking about this, I wouldn’t even be making work about it. I like admitting that the work is a work in progress, because I feel that a lot of times in critiques, you show work and you have this confusion of stuff because you are in progress. And people critique it so hard, almost as a final. And I find myself thinking, this is not the final. And even the final is not the final. I think it’s because school is such a mix of different kinds of people and work.

MD: When I talk about my work, I describe it as “time-based” and “process oriented”. Because a lot of it comes down to exhibiting and talking about all of this stuff and these random things. It is walking through the process of making it.

DC: When people say to me that they don’t see the connection, I think about how it’s important for me to make the viewer do work. I never just want to give it to the viewer so easily.

MD: What I really picked up from grad school is that there are so many different ways to approach making work. With some people it’s about control and having an idea and executing it, and with some people it’s more open and allowing them to flow. Some people never take a picture and just use others’ work. It’s all these ways of looking at it. Some people are more literal, some are less.

DC: I was having a conversation with someone who said that their work is not about the pretty picture and aesthetic, that people might grab on to more immediately, compared to work like mine. Do you ever have those kinds of concerns about your work, where you almost have to put things in or make elements of it more commercial? Do you care about that?

MD: I think I come to a lot of my work visually. Grad school made me realize that I am interested in aesthetic beauty, and that I am attracted to a lot of things visually. I think it is natural in my work to have that. With the live stream sunset, I realized that I do want it to be approachable. By projecting it on to a window facing the street, I wanted it to be accessible. I’m interested in theory and the community of the art world, but also in accessibility. That comes in all different forms – some people use humor, or subject matter. And I think I’m using it in aesthetics. It’s just a choice.

DC: Lastly, can we just talk about the kind of research that feeds your work?

MD: I’m a huge reader – I am an only child and both of my parents worked a lot when I was little, and I was left to read, and I was a voracious reader. I find a lot of my work comes out of things I read and it spans the gamut of literature to the newspaper. When I was thinking about my aura project, I had picked up Josef Albers’ Interactions With Color, and I tried to fit it into the project but wasn’t sure how, and I was looking at how the aura cam was made, which led me to this soviet technology of the Kirlian camera. I had all these pieces and couldn’t line them up. I went to Berlin this summer and I took an issue with the New Yorker with me that i hadn’t gotten to. There was an article about translation in it. I have always been interested in this idea of words that can’t be translated into other languages. There was a tiny paragraph on this German term dasein which means “the self” or “the presence”. It’s a very german word that comes out of Heidegger. That ended up being what sparked the video and all the things that came after it. So it was just this little section of a broader article.

DC: I love the idea of untranslatable words. I thought about something during a psychedelic trip once when my brain was going a mile a minute. There are so many things I wanted to say that I just started to think, “Is the English language enough or capable?”

MD: Exactly. There’s something inspiring in the disconnect when you can’t line the two up. And if you make work around it, then it becomes about experience, and something that a language can’t say. But that sometimes visuals can. But it’s always trying to build it up so that it does.

Duzant currently has an exhibition at,

LIFT OFF / Fridman Gallery

2014 NYC Photography/Video

January 30 – February 28, 2015